From building the world’s skyscrapers to creating the perfect fitting shoes, precise measurements matter. Yet we often take for granted how measurement shapes everyday life.

Humanity has always practiced some form of measurement science, known as metrology. Our ancient ancestors sought to understand the world in terms of length, volume, mass, and more. But the path to global measurement standards – namely the International System of Units (SI) – was long and complicated.

These days, a unit like a centimeter or a kilogram is the same quantity all over the world, but this wasn’t always the case. For thousands of years, humanity had few universally accepted rules regarding measurement, which made it difficult to trade, communicate, and make scientific advancements. It was a far cry from the modern standards that influence much of our daily lives.

Weighing of the Heart from the Book of the Dead. Credit: Wikimedia

So how did we develop and implement a standardized system utilized around the globe? Our story starts about 5000 years ago, dating back to the first evidence of standards in the ancient world.

Metrology in the Ancient World

The concept of measurement wasn’t invented in a singular time or place in history. Rather, ancient civilizations around the world came to unique conclusions on how to quantify things like weight, length, volume, and time.

The Harappan peoples of the Indus River Valley in South Asia created one of the first examples of standard measurements, dating back to about 3500 BCE. Uniformly sized bricks, which appeared in baths and drainage systems across cities, serve as evidence of some kind of regional agreement regarding the dimensions of building materials. While the way these standards were enforced and applied remains a mystery, we know humanity has been on a quest for metrological consistency for more than 5000 years.

A Replica of an Egyptian cubit. Credit: NIST

Around 2900 BCE in ancient Egypt, the cubit became a government-recognized standard under the pharaoh Khufu, who oversaw the construction of the Great Pyramid of Giza. Today, it’s widely recognized as the first recorded standard length of measurement. One cubit equaled the length of the pharaoh’s forearm, a unit that authorities materialized into a physical rod artisans and builders could use at their worksites.

The Great Pyramid of Giza’s nearly perfect angles, with each corner creating a right angle within 3/1000 of a degree, are not coincidental. The Egyptians realized the value in standardizing a unit for the sake of precision, rather than relying on abstract descriptions to design and build grand structures.

For example, many early measurements around the world relied on parts of the body, like hands or feet, which often vary from person to person. The ancient Romans and Greeks used feet and hands to measure, but like the Egyptians, they standardized these measurements across regions and throughout time periods to ensure consistency. Even today, countries like the United States use feet as a unit of measurement, but we now specify that one foot is exactly 12 inches or 30.48 centimeters.

Predictably, the fact that every civilization had unique systems of measurement resulted in challenging trade conversions. These challenges born from inconsistent units of measure continued for thousands of years, and it wasn’t until the 18th century that we saw the first substantial attempts at setting international standards.

The Rise of Regional Measurement Systems

After the fall of the Roman Empire in 476 AD, Europe changed dramatically. New societies and kingdoms formed, and so did new regional measurement systems. Many towns erected statues or plaques in the public square that could be used as a reference to measure objects, especially during trade. However, a given unit could measure several centimeters more in one city compared to another, even if the units shared a similar basis.

For example, medieval Dubrovnik, Croatia used a unit known as the Dubrovnik ell. It was based on the forearm measurement of a statue commemorating a Charlemagne-era hero known as Orlando (Roland) the knight. There was a different Orlando statue in Bremen, Germany that formed the basis of another measurement standard known as the Bremen ell. However, people in Bremen used the distance between Orlando’s knees to form the basis of the Bremen ell. In modern-day measurements, the two ells are different lengths, too: the Dubrovnik ell is 51.2 centimeters, while the Bremen ell is 55.9 centimeters.

In medieval Europe, regional measurement differences weren’t the only thing impeding the realization of universal standards. Tradespeople often used measurements that differed from official royal decrees, so no one was on the same page about the value and parameters of a given unit. Plus, the value of a unit could change with the crowning of each new king. The rulers of the day had little success enforcing standards, and any attempt at measurement was generally a free-for-all.

In the 14th century, Europe entered the Renaissance period, prompting a boom in scientific thought. Early purveyors of the scientific method, like Galileo Galilei and Isaac Newton, relied on repeatable experiments to draw conclusions. This meant using the same parameters – including measurements – that could be consistently replicated, sometimes by other researchers. Without consistent, universal standards, scientists recognized they would be unable to guarantee accurate results from their experiments.

An 18th-century engraving of John Wilkins. Credit: National Library of Wales

There were some proposals to create universal measurements, such as one in 1668 by English clergyman John Wilkins. He came up with standard units for mass, volume, length, and area that could be used by philosophers. However, his system, as well as other similar ones, lacked the political and technological influence to be implemented on a larger scale.

This lack of universal consistency came to a boiling point in 1790 during the French Revolution. By the late 18th century, it’s estimated that a quarter of a million different measurements were used throughout France alone. The leaders of the new republic realized how measurement inconsistencies hampered trade, political influence, and scientific progress. So, they made it a priority to set new national measurement standards.

The Birth of the Modern SI System

The French Academy of Sciences set out to create standards for all weights and measures that would be used throughout the republic. The aim was to create a nature-based scientific system that was sufficiently logical, yet simple enough for use in daily life. Today, we know this set of rules as the metric system or the International System of Units (SI).

The big task for the French Academy of Sciences was to define standards for measurements like length, volume, and mass. They started with a unit of length, called the metre. The metre derives its name from the Greek word “metron,” meaning “a measure.” It became the basis of the entire metric system, from which all other measurements derive their value.

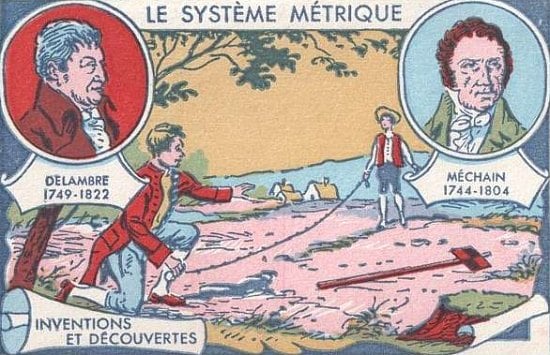

French surveyors Pierre-Francois-Andre Mechain and Jean-Baptiste-Joseph Delambre were sent to measure Earth's arc between Dunkirk and Barcelona in an effort to create a universal distance measurement. Their measurements had some errors, but the definition of the meter took hold. Credit: NIST

One metre equals one ten-millionth of the distance between the equator to the North Pole. 18th century scientists calculated this from real-life measurements taken on an expedition from Dunkirk, France to Barcelona, Spain. Knowing the exact latitudes of these two cities allowed them to accurately appraise the distance between two points that were directly north-south from one another. That information was enough to extrapolate the distance from the North Pole to the equator – though we now know that the original estimate is slightly off, rendering the metre about 0.2mm shorter than it should be.

The French government officially adopted the metric system in 1795, but it wasn’t until 1840 that it became mandatory for all citizens to use it. The metre and its counterparts weren’t warmly embraced by everyone, given that people were gradually forced to divest from older, more familiar forms of measurement. However, other nations slowly began to adopt the metric system after France mandated its use, giving way to a new era where measurements would be uniform across borders.

The Convention du Mètre (Convention of the Metre) in 1875 marked the first major agreement between nations to collectively adopt the metric system. 17 countries, including the United States, were involved, and soon acquired their own primary standards to use within their borders. By 1900, 35 countries agreed to adopt the metric system. Now, it’s the standard for almost every country in the world. Even the U.S., which primarily uses United States customary units, still teaches the metric system in schools.

The Future of Metrology

The 1875 Convention of the Metre paved the way for another important development in metrology: the establishment of the International Bureau of Weights and Measures (Bureau International des Poids et Mesures, or BIPM). Today, the bureau standardizes global measurements for all units that can be traced back to the SI.

Meter bars like these platinum-iridium ones were the standard length measures until 1960. Credit: NIST

The General Conference of Weights and Measures, the decision-making body for the BIPM, meets every four years to discuss potential changes to standards. Sometimes that means redefining a unit, which was done with the kilogram, ampere, mole, and kelvin in 2018. Other times, the meetings can result in adding SI terminology that encompasses the needs of new tech, as the conference did in 2022.

Any large-scale changes from the BIPM are significant and have a ripple effect on almost all scientific fields. But measurement standards aren’t set in stone – they need to be verified and updated time and time again. That’s just good science, and it also upholds the goal of metrology: to measure as precisely as possible.